In today’s creative industrial complex, certain entities emerge with such enormous clout-mass that nothing seems to escape their gravitational pull.

Let’s call them apex predators.

Any and all “creative” can be subsumed by these predators. Suddenly everyone you know is working for them (openly or secretly), or claim that they will be soon. They’re collaborating with everything; brands, artists, designers, corporations. Some of these collaborations make sense, many of them don’t. They appear to be insanely profitable while also being valorized by gatekeepers of high culture (curators, critics, the cuntiest people you know…).

“We’re all working for Kanye,” said Mat Dryhurst in 2017. And at some point it was indeed Kanye. But by definition, an ecological niche can have only a single entity sitting on top of the food chain.

There was a bit of a scramble for the place at the top over the last decade, with Kanye, Virgil Abloh (our dear friend, RIP) and Balenciaga under Demna Gvasalia, all vying for the top spot. Now in 2024, it is safe to say that Demna emerged as the undisputed winner.

After dominating the creative, clout, and content industrial complexes for the better part of ten years, it seems that Balenciaga’s reign as culture’s superpredator (no pun intended) is now past its peak. We thought it would be a good moment to riff on some of the key dynamics and tactics that fueled its dominance.

This is not meant to be the definitive brand analysis of Demna’s Balenciaga; that will be a momentous task for someone else at a later date. Instead, consider it the AW24 Balenciaga brand check in, brought to you by Nemesis.

1.

Cristobal Balenciaga established a set of house codes that persisted through successive generations of designers and creative directors. Alexander Wang’s unsuccessful stint at Balenciaga deviated from these codes, tearing down the house (so to speak) and creating an open space for a new vision to be instilled by Gvasalia.

Under his direction, Balenciaga opened the floodgates for all creative industries to influence and effectively become a part of fashion while the industry was at peak relevance.

Along with making fashion indistinct from art, music and advertising, this shift also carried culture professionals and the brands they love into Balenciaga’s world.

The process that led there – brand collaborations, artist collaborations, a general overload of crossover marketing – wasn’t itself new, but Balenciaga took these methods to an extreme, making appropriation an essential code for the brand. Collab culture, art x fashion and slasher institutions like the Prada Foundation were all antecedents in an ongoing process that reached its boiling point as Balenciaga rose to a new level of prominence.

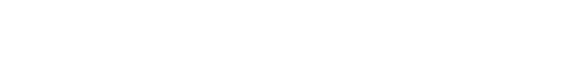

In Balenciaga's world, fashion’s more nuanced references and subtle inspirations were thoroughly cooked off, transforming looks into memes. Many of these new codes were based on taking an impossible “ugly thing” from the margins of culture and mixing it back into fashion, but done over and over to an aesthetic breaking point.

Big shoes

Bug eyed glasses

Oversized bombers

Slack shouldered suits

Erewhon, Ebay, Offset, Arca, Skinheads – anything could be frictionlessly interpolated into Balenciaga. At peak relevance, the brand’s instagram was essentially a collection of random clouted individuals wearing self-styled looks sent to them in the mail. These selfies produced a cast of characters and presented an exceptionally laissez faire form of clout bombing.

This was meme logic, using a brand as a deep fryer that could add a layer of ironic detachment to everything. In doing so, Balenciaga was tuned to the internet, using these new codes to attract the hyper culturally literate and illiterate alike.

For the illiterate, the end results were simply fire. For the hyperliterate, it was like being let in on a secret, a dynamic we unpacked in our 2020 memo The Umami Theory of Value:

“Throughout the history of human civilization, luxury was premised on being expensive, meaning it resulted from investing an unreasonable amount of work, material or other scarce resources into the making of a thing.

But today’s rich [...] wear $500 cotton t-shirts with inscrutable references and visual motifs pulled from a smörgås-moodboard that makes little “sense” in any generalizable way. The t-shirt’s price clearly isn’t a function of its material makeup, but rather a result of some form of manipulation of meaning associated with it. But because meaning is infinite, it can only become a luxury once it carries the illusion of scarcity.

Meanings that only a few have access to are secrets. In the absence of meaning, the illusion of a secret is created by imposing a subcultural barrier to entry where only through an opaque process of scene work can one ‘get’ it. Alternatively, they are wrapped in the veil of an elusive X-factor, to which only a privileged few, i.e. the creative director, have direct access.”

Balenciaga carried within it an metacommentary about how fashion works, and this bell curve approach to critique attracted fashion nerds as well as the tech elite who rejected fine art and embraced NFTs. People wearing Balenciaga got to participate in memeing everything from Bernie Sanders to My Little Pony into oblivion, which was unto itself a kind of “advanced” cultural position, at least on the surface.

Whether it was club culture, gaming, commercial partnership, or the expanded cast of characters drawn from far corners of the internet, Balenciaga used its reach to drag and drop artists, musicians, reality stars, etc., into an industry that had historically maintained its value by keeping its doors shut. “The world of Balenciaga” grew to encompass performance, design, art, architecture and everything else.

2.

Balenciaga became a form of vore porn, eroticizing its consumption of stars, symbols and subcultures. People enjoyed watching things become Balenciagafied, fetishizing the way in which the brand swallows up ideas and reproduces them.

While Balenciaga did produce its own aesthetics and ways of working, the primary driver of value for its cultural influence has been to use the brand as a flypaper for ideas scattered across industries and subcultures. The entertainment value here was less about the novelty of new ideas and more about the perverse pleasure people experienced in watching it devour existing styles.

As the apex predator, Balenciaga has been able to consume and appropriate culture unilaterally. That is, things can be Balenciagafied, but not vice versa; Balenciaga can absorb you, but nothing can absorb it back. That’s because the brand has no essence beyond the gravitational mass of its clout. It is a transparent eyeball of a brand.

This is perhaps best exemplified Balenciaga’s Bel Air Bag, which bears an uncanny resemblance to the iconic Hermes Birkin. Or its leather jackets adorned with the words “no logo”, which either borrow from Naomi Klein, reference Cayce Pollard, or both. Once the brand eats other luxury brands and appropriates the most advanced forms of consumer critique there's little else left.

There’s a reason why Hillsong x Balenciaga would totally kinda make sense. BlackRock x Balenciaga would shock no one.

The apex predator consumes culture to maintain its status above it all. Yet the scandals that Balenciaga found itself mired in in 2022 showed the limits of what the brand could absorb.

3.

Demna’s Balenciaga was more a process than a distinct set of codes. It was a way of metabolizing culture into fashion → fashion into content → content into sales. This is what we call the creative industrial complex – a distinct outgrowth of the content industrial complex as dissected by Dena Yago in 2018.

The creative industrial complex describes how the contemporary culture machine evolved to serve the needs of clout-based digital marketing, in which fashion houses act as galleries, galleries act as performance venues, and institutions are transformed into hype houses. In this ecosystem, participants can seamlessly transition from one role to another (artist as designer, designer as musician, musician as critic, etc).

Art, music, fashion and advertising have long commingled and exchanged value, yet they have now functionally become the same thing, allowing your status in any field to be transferred laterally into an adjacent practice. This sets the stage for all creatives and “creative” (their output) to form shared ecosystems with an apex predator at the top.

In previous eras, people like Warhol became the gravitational center of pop culture by bringing advertising and branding into music and fine art. As that path became more and more common the novelty wore off and creative fields were permanently distorted. Today Stanley Tucci is a food expert, Pharrell is a creative director. We all find ourselves asking, “what the fuck does Lady Gaga know about polaroids!?” People with status are consistently out of their depth creatively, dabbling in practices they barely understand yet somehow positioned at the top of their field.

This professional domain transfer allows athletes to launch makeup brands and performance artists to become stage designers, and for a time it positioned fashion as the primary medium through which culture flowed. It helped fashion shift from exclusivity and an insistence on its own distinct codes of value into a mimetic hype machine where “anything goes”.

Across different eras, different forms of cultural production reign supreme. For a time contemporary art captured the hearts of a generation. In other eras this was theater and music. In the currently expiring era, it’s fashion.

The more people have gotten into fashion, the more its occult energy and gatekeeping qualities have been abstracted and refined by its participants. Styles and creators multiply until it all becomes so niche and maxed out that it's irrelevant in its illegibility. During Balenciaga’s reign, fashion itself became about subsuming culture into its world. Now, however, all of culture works like this. The meta has been redistributed across various “cultural institutions” and branded hype houses.

4.

The right amount of absurdity and left-field silliness can now endow any ordinary luxury item with viral popularity. The Chopova Lowena Mayonnaise Bag, The JW Anderson Pidgeon, the consistently hideous MSCHF shoes – they all grasp at the simple arithmetic popularized by Balenciaga.

On paper, the codes that made Balenciaga the apex predator are easily deciphered and imitated, but in reality it takes more than 1:1 reproduction to capture the energy that fueled its generational run.

1980s comedian Gallagher rose to fame by smashing watermelons on stage with a hammer. He was so successful that he attempted to franchise his act by selling it to his brother (Gallagher Two). When it turned out there wasn't enough demand to sustain both Gallaghers, that brotherhood quickly turned to rivalry.

The relationship between Demna and his rival brother Guram is somewhat more complicated than this. While Demna’s Balenciaga toys with the trashy, his brother Guram’s goofy imitation of both Demna and Balenciaga via his own style and his brand Vetements is actually trashy. Therefore Guram’s work is, in a sense, more culturally authentic.

5.

The point of writing this quick analysis isn’t to claim the Balenciaga is “over,” culturally or financially – nor that it would be “so back” any time soon. (It’s always interesting to take a peek at the Kering annual reports. For all its mindshare, Balenciaga doesn’t even get its own financial line item, like Gucci, YSL, or Bottega Veneta does; it’s merely a fraction of whatever makes up the numbers of “other houses”.)

No, instead we’d like to posit three things.

a) Balenciaga had a generational run

b) it was significant and involved some interesting mimetic tactics

c) fashion itself is now past its peak and some other form can now claim its spot on the top of the cultural food chain

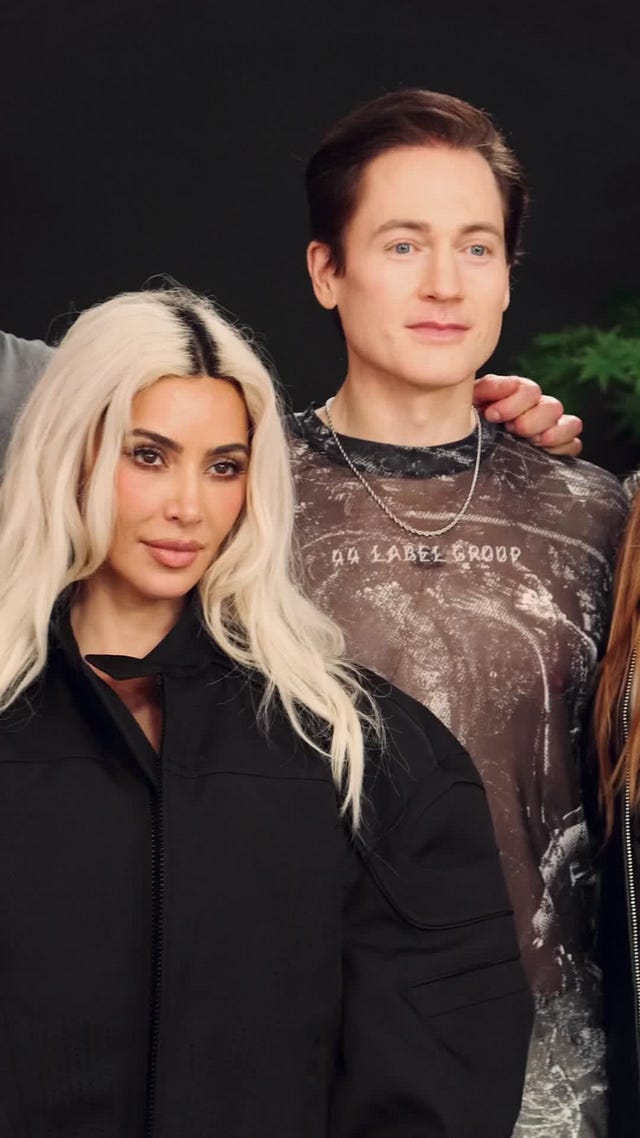

Regarding C, who or what could this be? This remains to be seen, but it certainly feels like the ascendance of the health-and-longevity industrial complex could lead to a decade of its dominance. Maybe it’s Bryan Johnson? His T-shirt at a recent Kardashians meeting, bearing the logo for 44 Label Group (owned by Matteo Milleri aka EDM artist Anyma aka boyfriend of Grimes, and the founder of New Guards Group Claudio Antonioli), certainly seems like a relevant data point or weak signal. A Balenciaga DON’T DIE capsule collection would be a fitting way to pass the baton.

Demna didn't exactly win. Virgil died and Ye essentiially died/killed himself. Fascinating stuff though.

Correction : 44 Label Group is owned by (Max) Kobosil in partnership with Antonioni. Anyma did a collab capsule collection with 44 Label Group.