When so much AI-generated media and algorithmic consumption warp everything into content, we can all agree that brands seem increasingly diffuse, less of a thing and more of a vibe. At Nemesis HQ, we’ve been asking ourselves: what is the future of branding in the age of slop?

The provocation for this particular stream of thought was a Tiktok video by brand strategist Eugene about branding in the era of brainrot.

This video declares that the age of brands as stories has ended. There are no more ninety second spots that tell a tale, he argues, now there’s only vibe, something more like sentiment or affect – what's picked up in a crowded feed, two or three seconds between footage of catastrophic climate change and a monkey who’s learned to do makeup tutorials. He gives the example of a Twitch stream: it may be too hectic to read the individual posts, but you can monitor the sentiment. You can catch the vibe. You can see if it's your vibe or not. You can vibe it out.

It’s true: a lot of people have been noticing an overabundance of vibes these days. Recent pieces in Airmail and New York magazine bemoan the hypertrophy of “vibe trends” like tomato girl summer, blueberry milk nails, hot rodent boyfriend, and social media fall. Online platforms stack statements like “this COS sweater has a Row vibe” into the horizon. The vibe effect resembles Mad Libs – you can fill in X vibe with Y item, and Y item with Z vibe ad infinitum. It seems that whatever it takes to define a vibe, relate a brand to it, and market against it has reached a sort of minimum viability. We could say it’s a breaking point, but is it really?

You can see this as the result of an era defined by the moodboard, or the inevitable conclusion of the Devil Wears Prada cerulean trickle down effect. New things – brands, products, trends – are increasingly defined in relational terms to such an extent that they become devoid of any unique story, character, or essence.

Moodboarding as a practice is maxed out. It’s become a nearly absurdist consumer hobby, and it’s part and parcel of our algorithmic reality, targeted yet vague. Similarly, slop can’t be meaningfully curated because there are too many actors, algorithms, and microtrends being expressed simultaneously, in too many automated iterations.

This situation has left a lot of us with the feeling that there’s no there there. We can all agree: “too much stuff looks the part but doesn’t quite feel the part.”

To put it another way: it’s clear that peak vibe has come and gone. Or that vibe is as mainstream as it gets, in this age of admittedly disjointed mainstream. Even the Instagram CTA urges you to articulate your current vibe. Perhaps an even more obvious example is the recent Camry campaign, centered on vibes. Would you be insulted if someone said your vibe is a Camry vibe? What even is the “vibe” of one of America’s most generic cars?

Brands may indeed be vibes today, which got us thinking about a few different ways that brands have been thought of historically. We can go through these quickly, more as thought starters than a complete review.

Brand as person may be the classic of the 20th century.

Emily was trained in strategy at Wolff Olins, the branding agency that defined the corporate personality and branding as a discipline distinct from advertising in the 1960s, so this one is very familiar to us, and is probably quite familiar to many of you as well.

When the brand is a person, an entity with a personality. The idea is that you can hone this personality in order to define your organization better and make more money out in the world. “All organizations have an identity whether they control it or not. A corporate identity programme harnesses and manages this identity in the corporate interest,” Wally Olins wrote.

Related to this are the “girl” of a fashion brand, the exuberant fiction of the cereal mascot, the voice of Siri (and now the personality of entities like Claude). This strategy allows people to bond emotionally with a brand in the same way they would with another person.

Brand as story is the other conventional frame that’s been very popular, as mentioned in the Tiktok that kicked this off. This one is all about using things like narrative structure and the hero’s journey to structure the way a brand shows up and communicates, and also using stories as branding opportunities. Brand “lore” is an updated subset of brand as story.

These stories tend to coalesce around a charismatic founder (Tesla and Elon), a social cause (Patagonia and the environment), even a countercultural position (SST records and punk rock). The depth of the lore is directly correlated to brand value. Consumers can become pay-to-play characters of the story.

Brand as pattern is about creating something that shows up iteratively in the world, rather than repeating messages rotely. This has classic examples, like Absolut ads, and more mimetic ones, where users take on the pattern and create the brand themselves (something that comes up often in conversation with Nemesis’s more decentralized clients).

Memes are an advanced form of this practice – everything from Pepe to Brat makes use of this repetition to create flexible and iterative meaning. Brands that rely heavily on UGC are often related to brand-as-pattern.

Brand as interface is from the theorist Celia Lury, who wrote Brands: the Logos of the Global Economy. She describes how brands are a way of interacting with the global economy in a way that goes beyond the rational order of price alone, introducing all these other elements – soft and hard – that stand in for sheer price and utility.

Lury argues that the “brand mediates the supply and demand of products through the organization, coordination and integration of the use of information”. Since “an interface is the organization of data by one system for communication of another,” she writes about how “the interface of the brand is revealing of some relationships” (i.e. between the consumer and the brand) “but it keeps others very well hidden” (e.g. the consumer and the workers who create the brand’s products).

Then there’s brand as world, the less eggheaded, more contemporary version of brand as story. Worldbuilding as a brand activity feels intuitively more digital and immersive, less linear than straight narrative.

Many luxury brands employ this practice to help us imagine a world of accessible wealth where people are more beautiful, more free, more actualized. Disney offers an accessible, albeit more fanciful version of this practice – creating an actual destination with its own culture and characters. In either case, the brand is a portal that gives you partial access to an alternative reality.

Brand as coherence is another more philosophical way of looking at brands, one that Nemesis-friend Michael Rock of 2x4 talks about a lot. In this world the brand is the je ne sais quois or x factor that makes everything fit together. It’s the systematic principle itself.

This coherence can be emotional…

“When we talk about a strong brand, what we mean is that it consistently delivers the emotion it promises. The most successful brands, or at least the ones everyone emulates, have the knack for using design to produce an emotional coherence that spans from content to product to experience. Think Apple or BMW or Chanel. Not everything has to look alike, but it all has to feel alike. Whenever we encounter them we get that familiar brand sensation. That tingling tells you it's working.” (Michael Rock, Hooked on a Feeling)

Or technical…

“I know that [branding] is an incredibly distasteful term in cultural and academic organizations, but like it or not branding has become one of the major organizing principles of the world as we know it right now. States have brands, corporations have brands, people have brands, institutions have brands — everyone’s talking about that, and when they talk about brand, they may all be talking about different things, but I think it’s a way of thinking about this idea of assembly…I would say maybe that branding is this act of assemblage that creates seemingly coherent entities.” (Michael Rock, Berkeley design lecture)

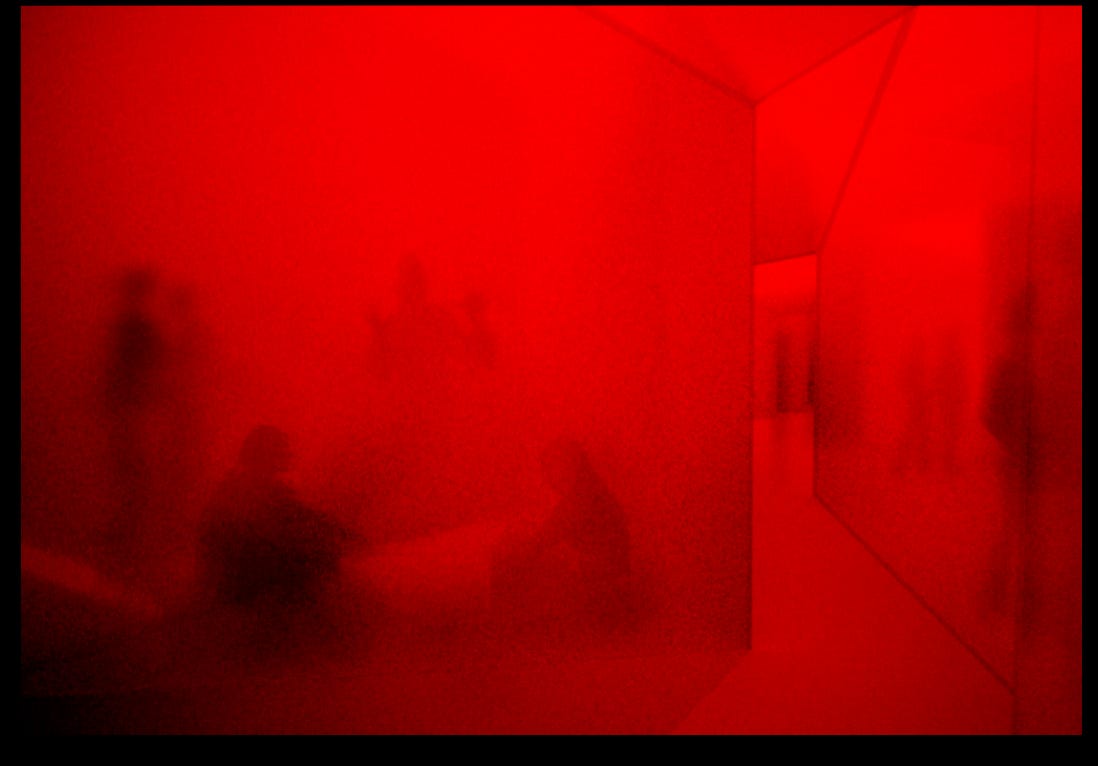

Then, finally, there’s the brand as vibes. These are not just brands that have us asking what the there-there is. They’re also brands like Marc Jacobs’ Heaven, which has brought together disparate objects that fit a sort of dreamy Gen Z moodboard to great effect, creating new life for what was quickly becoming a legacy brand. Then there’s A24, perhaps one of the greatest vibe brands of them all.

At this point you might be asking yourself – what is a vibe, actually?

Vibes have been theorized by some notable academics, specifically two favorites in the Nemesis world, Peli Grietzer and Robin James.

The theorist Peli Grietzer makes an important link between machine learning and vibes in his canonical 2017 essay, “A Theory of Vibe.” The machine learning technology of autoencoding sniffs out alignments among sets of objects, and this, he argues, is analogous to when a person catches a vibe. As Greitzer puts it: “suppose when a person grasps a style or vibe in a set of worldly phenomena, part of what she grasps can be compared to the formulae of an autoencoder trained on this collection”.

Robin James builds on this work to clarify that “algorithms aren’t perceiving styles or genres. They’re perceiving vibes, where the alignment among data points matters more than the contents of that data”. More significantly, she argues that vibes are “a way for people to perceive themselves and their world the way algorithms perceive things.” She uses the example of “liminal space vibes,” among a disparate set of images of empty lobbies, elevator shafts, and waiting rooms. “Vibes are alignments or orientations that make some perceptual contents more palpable and some perceptual contents less so.” Certain things stand out, other things fall back. She argues that “vibe will increasingly become the language or discourse through which we negotiate the tensions that have been more traditionally negotiated through genre or style…”

Perhaps even more revealing is this Reddit thread (from an exchange about learning English, which is very indicative of the core sense of language): vibes are something we feel, and have something to do with a sense of recognition or belonging.

In a sense, vibes are procedurally generated, created by following resonant patterns and associations rather than by directly expressing new ideas or unique sentiments. The value assigned to brands built on vibes is similarly transitive – if you like X you will probably like Y.

In the best cases, a brand can create and embody its own ineffable vibe that imbues all of its products and endeavors with a sense of magical value. Seeing the new A24 film is more about experiencing a new iteration of the brand than it is about the movie’s actual plot, cast, or story. Fans want to see a particular sensibility applied to the world around it.

In the worst cases, brands melt into slop. They bear an uncanny resemblance to some other real thing (a Yeezy-type slide, a Playboi Carti type beat), while laying bare the algorithmic mechanics that created them.

If brands as vibes are maxed out, the point of this essay is to imagine what might come next. What – if anything – could cut through the brainrot and the malaise, show up as legitimately progressive or fresh?

As a friend said recently, regarding a piece of merch in his peripheral vision: the consumer has been through a lot.

When a brand is a person, you have an emotional connection with them (they also have rights: see Citizens United). When it's a story, it entertains you and holds your attention. When a brand is a world, there's immersion and escape. When it's a pattern, you can replicate it and play with it.

When it's a vibe, it gives you a feeling and a fleeting sense of coherence and possibly of belonging, the sense of fitting with something, a flash of recognition. But the set-of-things that constitutes a vibe field also has open edges, borders. It's blurry and can be expanded. (This is why dupe culture relies on vibes.) The vibes bleed into content – more and more messily – till the original signal ceases to exist, or to make any sense at all…Eventually it all dissolves into an amorphous, vibey puddle. At this point, everything is kind of like everything else.

Conventional wisdom says to do the opposite, buck the vibe with something fundamentally anti-vibe. So in the past you'd go for heritage, but heritage and authenticity are just vibes now too.

It may help to recall this recent post by @nstlgiaxpress, that says taking a picture with a Birkin bag is easy – whereas maintaining a yuppie deluxe lifestyle with two kids is hard.

If you think about it, vibe overload is the inevitable outcome of conspicuous consumption in the algorithmic feed. Too many pictures with too many Birkins at too quick a clip. So again, conventional wisdom would say do the opposite: if things are too visible and exposed, then become private, secret, gatekeep.

But there's always some signal – the black card, the news story that you're not allowed to take pictures at the fashion show, the closed door at the member's club. Privacy becomes a vibe too (see also: stealth wealth).

With all this in mind, the key to successful brands after vibes may be in creating...

something dense and irrefutable: a brand that flaunts itself as proof of work, that makes clear the amount of real information and human effort that went into creating it, that can’t become blurry.

The brand is labor itself, a direct expression of the work that produces it.

something exceptionally simple – logo only, that is, just one coordination point…or better yet, a ticker, a single letter, a point of pure speculative energy. Something so singular it can’t be spun off into iterations, but due to its singularity, can freely attach to and feed itself by anything and everything.

The brand is an atom, a particle, a single-cell organism.

something like dazzle, the makeup that helps a face escape facial recognition software: something so incoherent it can't be read by the model or algorithm, something that cannot be expressed as or compressed into a vibe.

In this case, the brand is noise, something rule breaking that jams an orderly system of meaning / value.

In The Substance, Demi Moore takes a drug to make one perfect copy of herself, but if she uses that copy to produce other duplicates, it creates a monster. When brands are built on vibes and vibes are built on other vibes things default to a ponzi dynamic where value is created by the production of the next thing. Everything is inspo but nothing actually gets made. This is very different from how branding was traditionally approached, where design and strategy were used to produce something singular, iconic and enduring. Where will algorithmic commerce take us next?

If you found Grietzer's theory of vibe compelling, you may also find the following's account of "ambient meaning" to be of interest: https://thelastwave.substack.com/p/the-network-is-the-territory

🎯