NO NEW MUSIC (CULTURE AFTER YOUTH CULTURE)

A trend that's likely not going to reverse any time soon

Our next workshop, Nemesis Writing Protocol, takes place next weekend, July 19 and 20. It’s a shorter enrollment period than usual, so make sure to sign up if you’re interested! We would love to see you there.

Recently, while chatting about the state of the music business with an industry veteran friend who works at a major indie label, he said something surprising:

“All of our acts are having their biggest records now”

Initially, this felt like a narrative violation. Wasn’t the music industry, especially what remains of its independent parts, in a deep state of crisis? Yes and but also no (but also yes). Continuing the conversation, his next statement aligned more with expectations:

“We’ll only sign artists with an existing following. None of the tools we have for breaking new artists work anymore.”

So what’s going on here?

Some context: the artists in question – the ones having their biggest records now – are all seminal “big indie” acts who came up during the 2010s. This makes sense, as the 2010s are also an important cutoff point: if an artist captured the minds of an audience before the fragmentation of attention across algorithmic feeds, it’s analogous to snatching a rent-controlled apartment with a permanent contract 15 years ago. There were a lot more apartments available back then as well as unoccupied slots in impressionable young brains.

Like all those who arrived in e.g. Berlin 15+ years ago who are *never* going to move again, the 2010s (and 2000s, 1990s etc.) artist permanently squats a memory slot in our collective psyche – rent-free.

Trying to break a new artist today with the PR tools of yesteryear is as futile as trying to find a decent apartment through official rental listings. For a cultural product to cut through the noise in 2025 one of the best strategies is trying to activate memories and a sensations of familiarity formed before the domination of algorithmic feeds, during an era of relative cultural coherence. Hence, the phenomenon of legacy acts having their biggest records now.

We discussed this permanent advantage that pre-algo-feed-era – and especially late broadcast era – artists and media IP have over newer entrants in our recent post Culture After Youth Culture. The core thesis: youth culture is no longer the primary locus of cultural influence. For better or worse, Millennials now hold the cultural center of gravity. There’s a growing disconnect between what we perceive as “youth culture” and the actual culture of young people. One concrete expression of this is Millennial youth culture’s refusal to die.

This thesis is distinct from – but related to – the observation that since at least the 2010s, art and culture at large have failed to capture, communicate or express a distinct sense of the now. And even less so, any compelling visions of the future. As many have noted, we live in a tightening nostalgia loop: reboots, remakes, remixes, reinterpretations, and references abound.

Ross Douthat recently interviewed the Antichrist, who lamented a form of technological – and by extension cultural – stagnation that we supposedly find ourselves in where we’ve given up our dreams of flying cars and eternal life via cryogenics. Ironically, this reminded us of someone perhaps as far from Peter Thiel as one can get: Mark Fisher (RIP), who used the same trope (the absence of flying cars) to evoke a sense of lost futures – futures we once were looking forward to that now have faded away from our collective imagination. Few diagnosed the chokehold of 20th-century culture distributed via 21st-century tech better than Fisher.

His 2014 talk The Slow Cancellation of the Future, in which music serves as a synecdoche for wider culture, is wild to watch in 2025 as so many of the dynamics dissected by him have only grown stronger. Yes, we still live in a temporal malaise, only messier. “Nothing ever dies” is still true and, quite incredibly, we’re surrounded by many of the same zombie forms than he was 11 years ago.

When analyzing or forecasting cultural trends, one simple heuristic is fashion-math: if X is in fashion now, expect non-X or anti-X next. Skinny pants yesterday, wide pants today etc. Fashion-math also underpins a hopeful prediction (or cope) that cultural stagnation will automatically be followed by a renaissance filled with cultural innovation. Or another example, related to the underlying dynamics of the waning influence of youth culture, fertility collapse will automatically be followed by a baby boom.

But sometimes trends are secular, epochal or permanent, driven by slow moving factors like demographics or deeply entrenched property interests. Undoing or reversing them can take a very long time. And sometimes trends don’t reverse. Many simply trend toward zero, never to return.

We’re not setting up a doomerist argument; we’re not saying we’re on an inevitable or even likely path to permanent cultural stasis or extinction. We’re just pointing out that cultural trends don’t always come with a built-in pendulum that would automatically swing back the trend feels overextended. And unless there’s an exogenous shock, we believe “culture after youth culture” – and its limited ability to produce a distinct sense of the new – will be with us for a while.

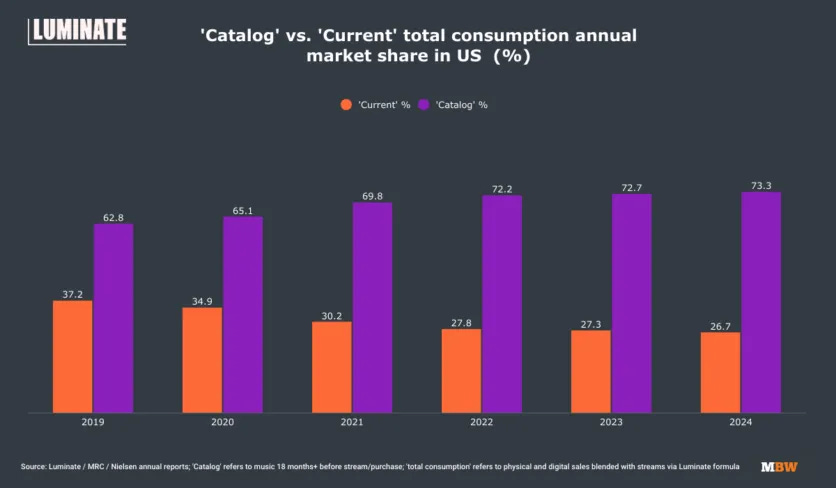

Riffing on Fisher, pop music is one of the great theaters of this stagnation. Over the past decade, we’ve seen a wave of high-profile acquisitions and consolidation of music IP. As catalogs owned by players like Hipgnosis, Primary Wave, Concord, and Warner are expected to yield royalties, their economic model favors old music over new. Once a fund acquires the rights to a song, it’s in their interest to license and stream it repeatedly rather than risk investing in something new.1

Functionally, this ossifies a pop music canon, with powerful incentives to promote and recycle the IP within it. These incentives are reflected in Spotify’s algorithm: old music up, new music down. Canon in, ex-canon out.

This also affects what counts as new music. Artists are incentivized to borrow, cover, or interpolate from the canon to align with the interests of major IP owners. (Recently an email from a forward-looking sync agency came across our desk, where they requested the artists they represent to shift their focus to creating cover versions – complete with tips how to “genre flip”, “emphasize the hook” etc. – of existing songs, to satiate the ad and film markets incessant demand for them.)

Here’s where the natural tendency to expect for the trend pendulum to swing back comes in: isn’t there a saturation point of old music and zombie media IP, where the baseline demand for novelty isn’t met anymore and these trends will need to revert? Perhaps. But it might very well be that that baseline is much lower than us enthusiasts can imagine – especially for an audience that has grown up under canon dominance and lower exposure to new music soundtracking the passage of time. Novelty might now be satisfied by the smallest perceptible deviation from what came before, rather than a full blown sonic revolution that makes us question what pop music even is. In fact, reduced attention spans are better served by minimizing the amount of new information coded into a song or cultural product.

“Imagine playing this to a Victorian era child” goes the popular meme suggesting that the child’s 19th century brain couldn’t handle the music (or other cultural product) in question because it’s so insane / cracked / intense / crazy. That could be true. But from the perspective of the Victorian child, nothing made since the mid 90s has really upped the level of musical insanity or novelty (perhaps with some rule-confirming Brazilian exceptions). It is also telling that we need to conjure an imaginary adolescent audience from 150 years ago to create a sufficient sense of implied difference between then and now. It’s a lot more shocking that’s there’s hardly anything from 2025 we could play a kid from the mid 90s to make their brain melt.

“The trend is your friend” means, all things equal, it’s better to predict a trend will continue rather than be on the cusp of reverting. That being said, nothing would make us happier than this post being the ultimate bottom signal marking the nadir of pop culture’s capacity to adequately express the new. But for now, we assume the fracking will continue as long as the bottom lines improve.

There’s a related point to made regarding the training data of large audio models (as well other media modalities) which bears close resemblance to canon inclusion/exclusion, but we’ll leave this can of worms for later.